By Nicole Bell, Galaxy Diagnostics CEO

3/10/25

While many people in the Lyme community are familiar with the three Bs – Borrelia, Bartonella, and Babesia – most people outside the community look confused when I mention these top flea and tick-borne pathogens. I understand their puzzled looks because back in 2017, I was confused too.

Even after my husband, Russ, was diagnosed with these three stealthy invaders, I focused all my research on Borrelia, the bacteria causing Lyme disease.

It ended up taking a tragic journey followed by years of studying the research to gain an appreciation for the complexities of all three pathogens – and that research is still unfolding.

In complex cases, co-infections are the rule, not the exception.

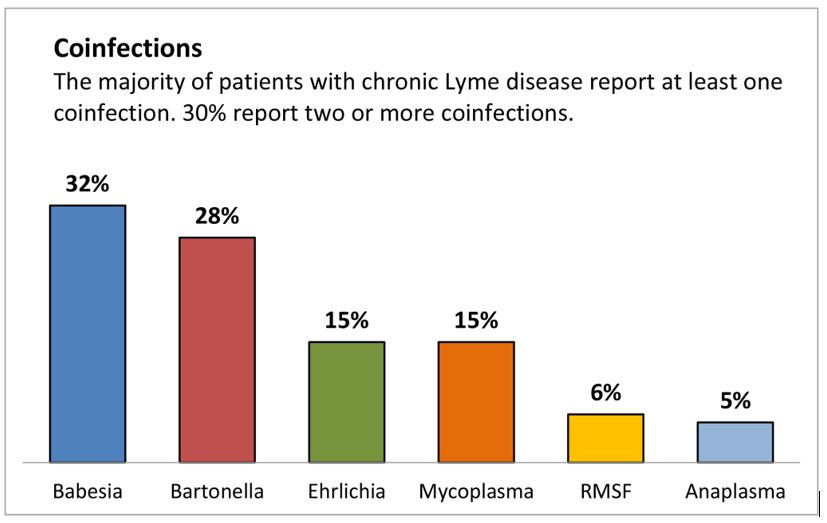

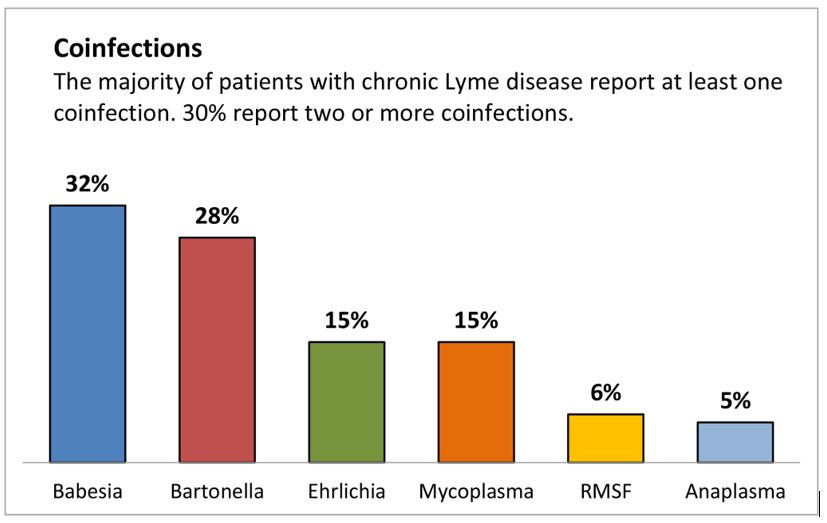

The first thing to understand when considering the three Bs, is that in complex cases, co-infections are common. In a survey of over 3,000 chronic Lyme disease patients published by LymeDisease.org, over 50% had co-infections, and 30% had two or more co-infections. Babesia and Bartonella top the co-infection list, each presenting in about 30% of chronic Lyme cases.

Source: About Lyme Disease Co-infections, LymeDisease.org

The second thing to understand about these pathogens is that calling them “Lyme co-infections” is misleading. All these pathogens – the other Bs and beyond – can be present without a Borrelia infection (past or present).

The problem is that many doctors don’t have these invaders on their differential – and it’s easy for a pathogen to be considered rare if you never test for it.

Rare disease? Or inadequate testing and data?

To understand the true prevalence of these pathogens, we need to dig into the details of each pathogen and how we count and test for them. For example, before 2013, Lyme incidence in the U.S. was estimated to be approximately 30,000 cases per year. Then, in 2013, the CDC looked at clinical records, laboratory reports, and public surveys and increased this estimate 10-fold.

In 2021, an analysis of insurance records increased the estimates again, and current data shows that approximately 500,000 Americans are diagnosed and treated annually. And since the standard of care test for Lyme leading to diagnosis and treatment is 40-60% accurate, even this number is likely underestimating the extent of the problem.

So, the question looms – what is the prevalence of the other two Bs? Are they destined for a similar exponential increase as we dig into the data? Emerging research points to yes.

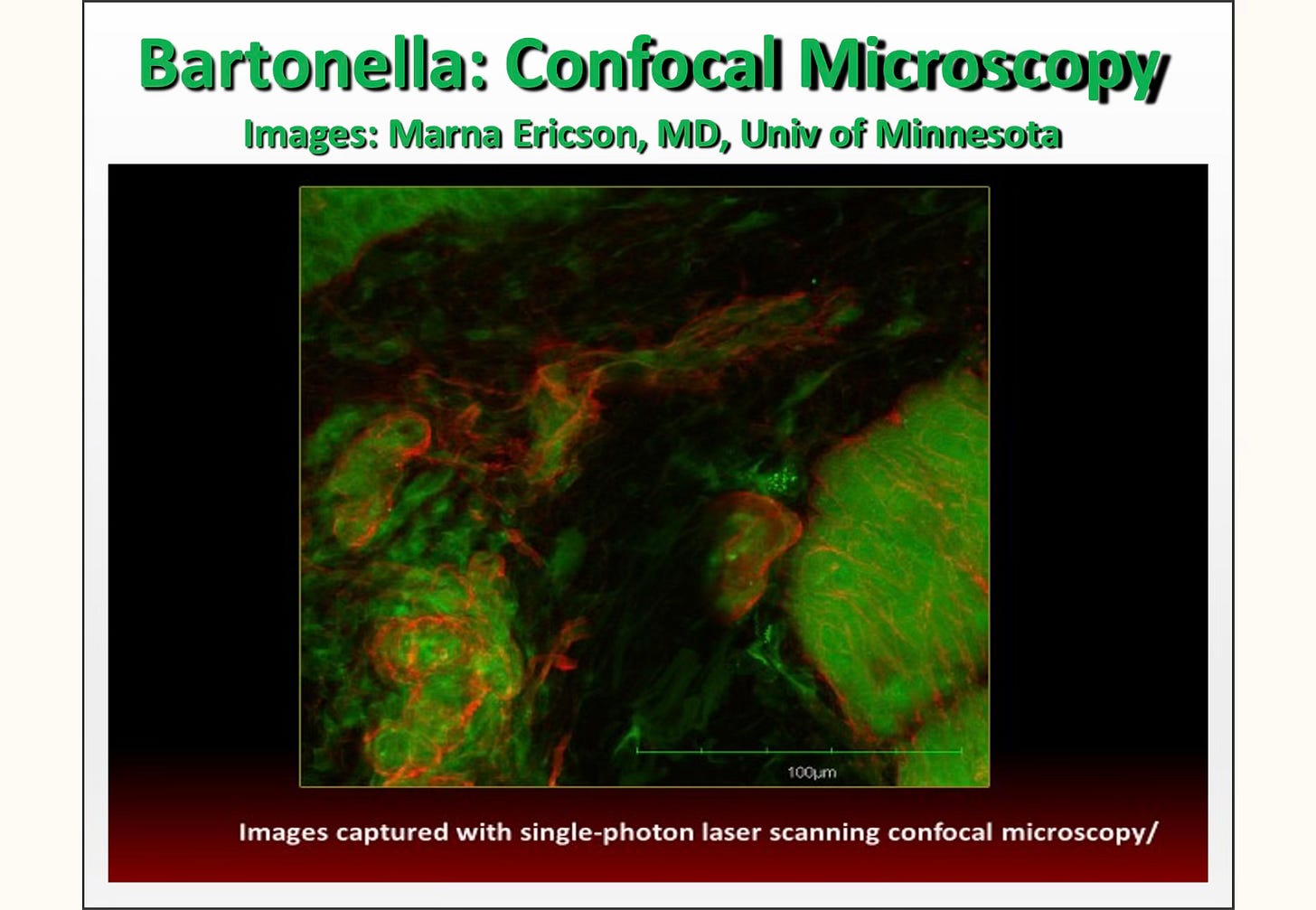

Bartonella – The Hidden Pandemic

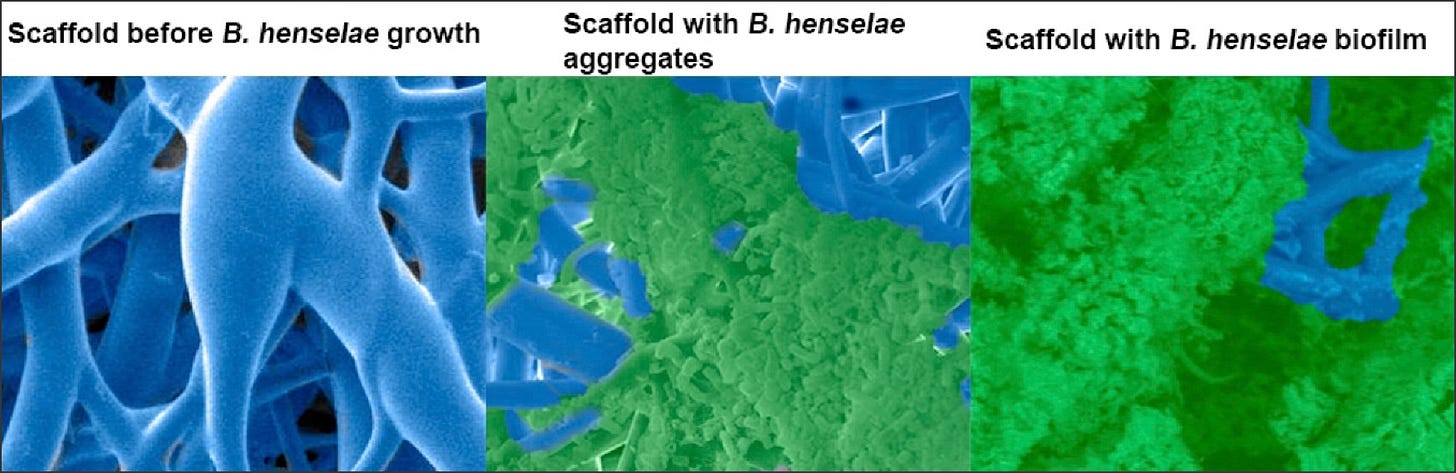

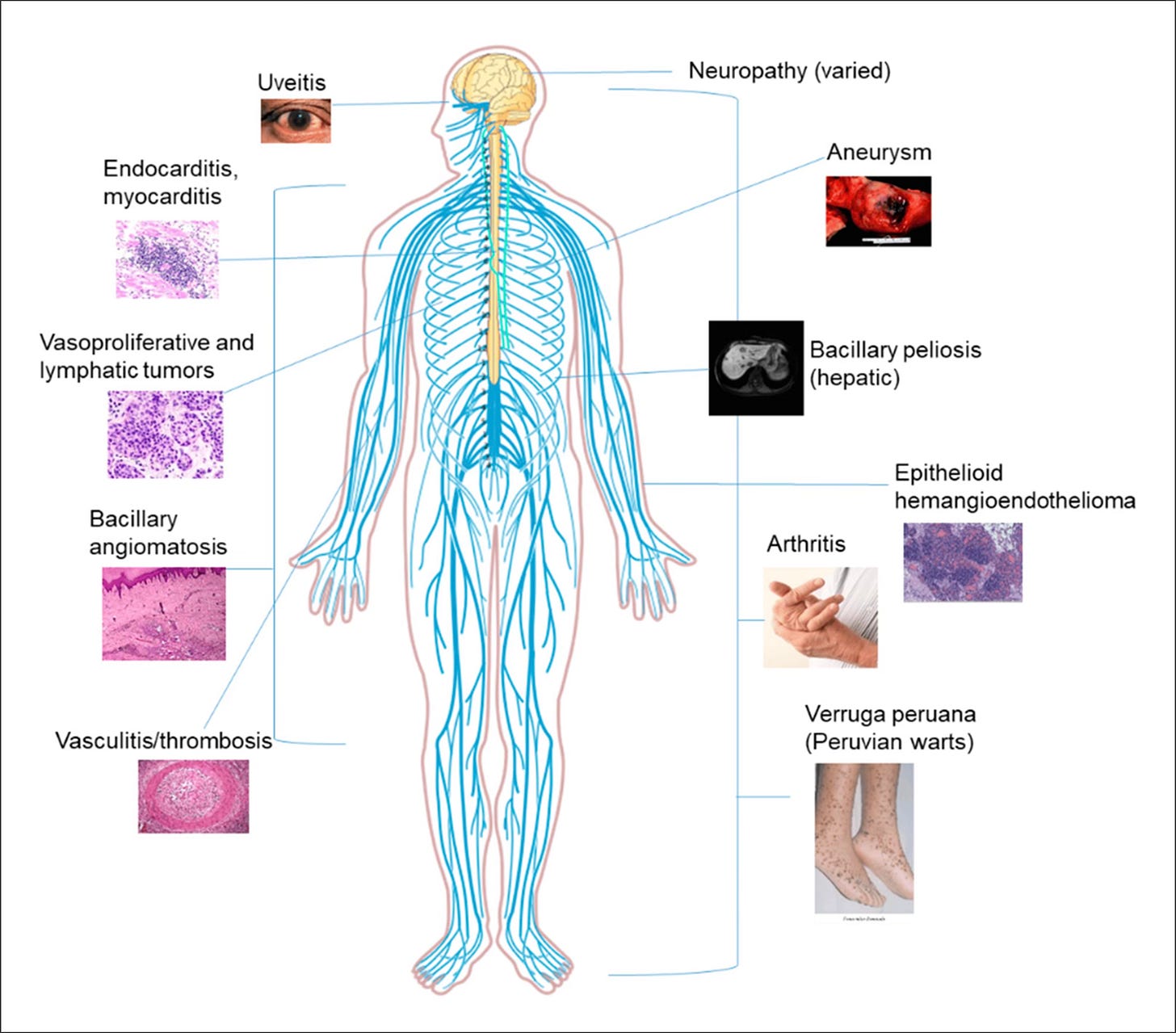

Bartonella is a genus of gram-negative bacteria that can infect humans and a wide range of animals. Googling the bacteria shows that it is the pathogen causing cat scratch disease or CSD, an acute form of the infection. But like Lyme, this pathogen has been associated with complex chronic conditions spanning multiple body systems, including the joints, eyes, heart, and brain.

Lyme disease has made people fearful of ticks, but Bartonella can be transmitted by a long list of biting insects – or vectors – including fleas, body lice, sand flies, and even spiders. Also, an underappreciated risk factor for bartonellosis is animal exposure, particularly exposure to cats, which are natural reservoirs of the bacteria.

In a study of veterinary workers, 44% were positive for Bartonella antibodies, and 28% had DNA of the pathogen detected directly from their blood. With approximately 66% of U.S. households owning at least one pet, the pathogen has the potential to be more widespread than generally thought.

Dr. Ed Breitschwerdt from North Carolina State University’s veterinary school has studied Bartonella since the 1990s. The advanced testing methods developed in his lab by collaborator Dr. Ricardo Maggi have uncovered key links between the pathogen and complex illnesses, such as arthritis, chronic fatigue, and fibromyalgia.

Neuropsychiatric conditions

Recently, using innovations in advanced PCR technology, the lab has made groundbreaking discoveries linking Bartonella and neuropsychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia.

The investigation into schizophrenia started the way many discoveries in medicine do, with one case. A 14-year-old boy – who we will call Michael – suffered from sudden onset psychosis and received a formal diagnosis of schizophrenia. Michael was referred to Dr. B’s lab because he had marks on his skin, called striae, consistent with a Bartonella infection.

Dr. B and his team used their advanced test methods to confirm that Michael was infected with Bartonella. Upon treatment with the appropriate antibiotics, his symptoms evaporated.

The case inspired Dr. Breitschwerdt to consider a hypothesis – what if other patients were experiencing psychosis because of a Bartonella infection? Bartonella can cross the blood-brain barrier and infect endothelial cells, contributing to neuroinflammation.

The hypothesis had merit. His lab partnered with the University of North Carolina to test 17 schizophrenia patients. Sixty-five percent of those patients tested PCR positive for the pathogen, compared to 8% in healthy controls.

A subsequent study with Columbia University on over 100 patients found that people affected with psychosis were over three times more likely to have direct evidence of Bartonella in their blood than unaffected controls.

PANS

And schizophrenia isn’t the only neuropsychiatric condition linked to the pathogen. Pediatric patients with Bartonella infections have been reported to develop Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) and symptoms like anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and cognitive dysfunction. Case studies have shown improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms following treatment of the underlying infections.

With over 3 million Americans battling schizophrenia and 1 in 200 children in the U.S. affected by PANS, Bartonella may emerge as the great hidden pandemic.

Babesia – the tip of the iceberg

Babesia is a tick-borne parasitic infection, often touted as similar to malaria, because both parasites infect and replicate within red blood cells and can cause fever, chills, sweats, headache, muscle aches, fatigue, and hemolytic anemia.

Researching Babesia on the CDC Website shows that under 2000 cases were reported nationwide in 2020. The CDC notes that most Babesia cases in the U.S. are caused by Babesia microti, with occasional cases caused by other Babesia species.

Using the same advanced PCR technology that drove clinical discovery in Bartonella, Dr. B and his team turned their attention to Babesia. They found that what we “know” about Babesia may only be the tip of the iceberg.

In 82 individuals the lab was studying for Bartonella infection, 22 (27%) were also infected with Babesia. Furthermore, the top Babesia species identified was not Babesia microti, as expected from CDC data, but rather Babesia divergens (considered rare in the U.S.) and then Babesia odocoilei (considered rare in humans).

Before Dr. B’s work, only a handful of case reports in the U.S. have ever been reported for Babesia divergens. Their best-in-class assay turned up 12 new cases in a group that wasn’t even targeted for Babesia studies.

Dr. B’s team also recently published a paper where an entire family – all five members and one of their dogs – tested positive for a Babesia-divergens-like species. Similar new case discoveries have been made for Babesia odocoilei. His work poses the question – are the pathogens really rare, or are we just not testing for them properly?

Genus versus species – why it matters

Genus and species are terms commonly used by microbiologists, but when I first entered the world of tick-borne disease, I didn’t fully understand their significance. The “genus” is akin to a family name, grouping related individuals – think Hatfields and McCoys. The “species” is like the first name, identifying a specific individual in the family.

Translating this to Lyme disease, Borrelia is the genus or family name, and Borrelia burgdorferi is the species name identifying the particular pathogen.

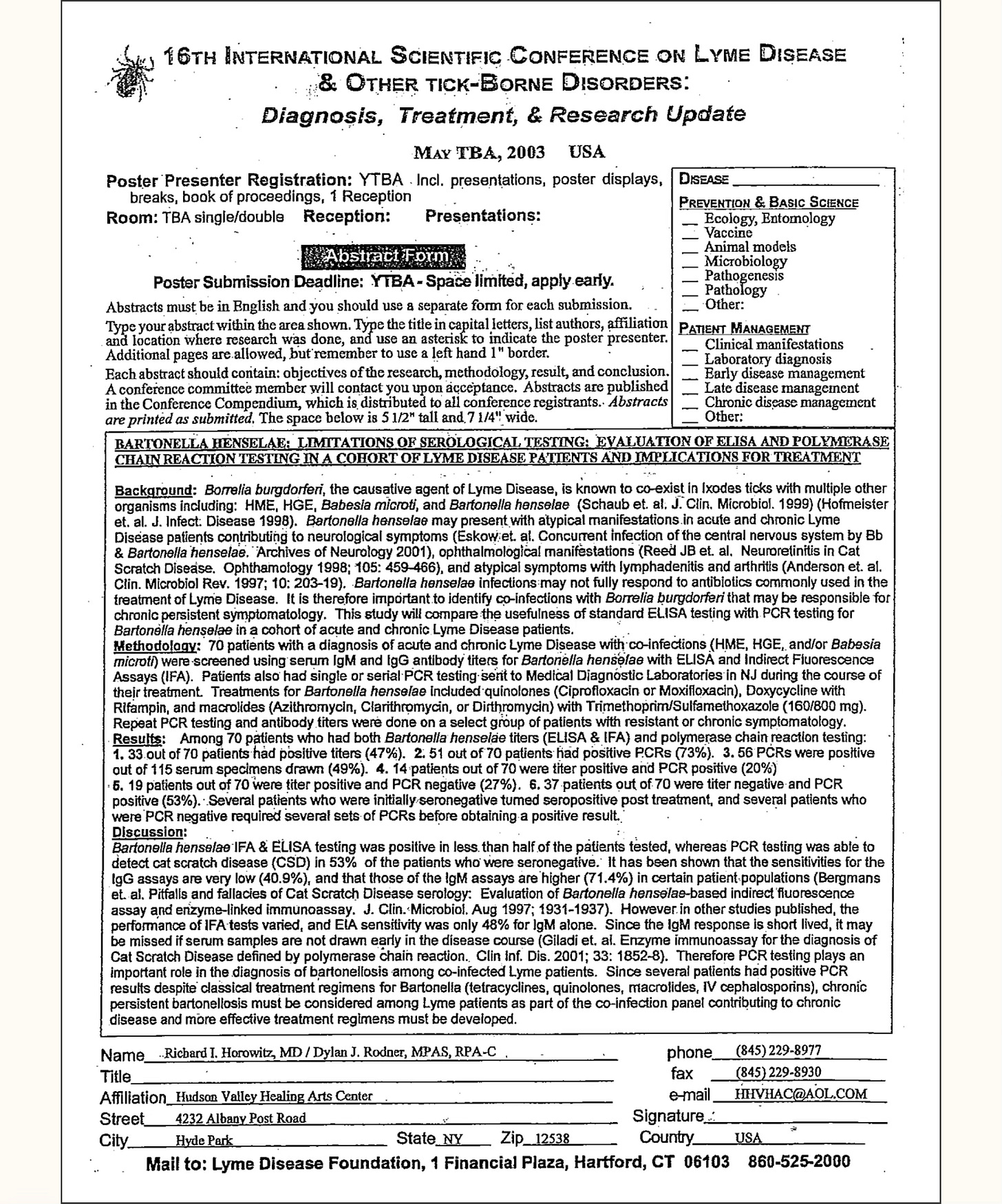

So why does it matter? The current commercial test methods for all three Bs generally use serology or antibody testing. These assays measure antibodies created by the host’s immune response to the pathogen. The problem is that antibodies react to proteins on the surface of the pathogen, and these proteins can vary depending on the particular species.

In other words, the patriarch of the Hatfield family, Anderson Hatfield, looked and dressed differently than his son Cap Hatfield. Thus, sending out a warrant and a picture of Anderson is unlikely to lead to Cap’s arrest.

Antibody testing is similar, and testing for Babesia microti, may not accurately diagnose a case of Babesia odocoilei or Babesia divergens. There are over 100 known Babesia species, with 15 of those confirmed in human cases.

There are over 50 species of Bartonella, at least 20 of which have been documented to infect humans and other mammalian hosts. Dr. B’s research and testing technology is redefining what we know about these pathogens. And until these tests are launched commercially, millions have the potential to be misdiagnosed.

Direct Detection for BBB is Launching at Galaxy Diagnostics

Fortunately, Galaxy Diagnostics was founded by Dr. Breitschwerdt, Dr. Maggi, and Dr. Amanda Elam to bring these diagnostic advancements to market. This month, Galaxy is launching its digital PCR, direct detection assay for BBB.

This assay has been instrumental in driving clinical discovery in Dr. B’s lab and will now be commercially available to practitioners. Top features of the assay include:

- Genus level detection, detecting each pathogen regardless of species.

- Ultra-sensitive, digital PCR, which increases detectability for low abundance pathogens.

- Multiplexed detection to provide three results in a single test.

The BBB assay is a blood-based assay that detects the DNA of each pathogen. The approach has previously been used only in a research setting, but the team at Galaxy has now validated the assay for commercial use.

Bartonella and Babesia – but what about Borrelia?

The BBB assay is a blood-based approach, and it is essential to note that blood is NOT the best matrix for Lyme Borrelia, as I have discussed previously.

Galaxy recommends its urine antigen test for Lyme since the concentrations of Lyme Borrelia are so low in the blood that a blood draw is unlikely to capture the pathogen in the test tube. And no matter how sensitive the technique is, if the pathogen isn’t in the tube, there is no way to detect it.

So then, why is Borrelia included in the BBB assay? The answer goes back to the genus versus species issue. While the species associated with Lyme Borrelia often hide in tissues and don’t free-circulate in high copy numbers in blood, the species associated with Relapsing Fever Borrelia do replicate to high numbers in the blood.

As a result, combining the BBB assay with Galaxy’s Nanotrap urine antigen test for Lyme provides optimal coverage for the top flea and tick-borne infections at the genus level.

Coming Full Circle – Avoiding Cases like Russ

After my husband Russ passed, the engineer in me knew there had to be better options. I immersed myself in the research and found Dr. B’s published peer-reviewed results. I introduced myself to the Galaxy team, and as I dug in, I became even more convinced that their technology would provide the clarity I craved as a caregiver.

In June 2024, I became Galaxy’s CEO to bring these advanced testing techniques to a broader market. We crystallized our mission to provide a new standard of care for diagnosing these devastating flea and tick-borne diseases. With the commercial launch of the BBB assay, we are one step closer to that goal. I know that Russ is watching – and smiling.

Nicole Bell, CEO of Galaxy Diagnostics, is also the author of What Lurks in the Woods and The State of Lyme Disease Research.

For more: