Everything That’s Known About Ehrlichiosis

https://www.news-medical.net/health/Epidemiology-of-Ehrlichiosis.aspx

Epidemiology of Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis is a disease caused by several Gram-negative obligate intracellular bacteria that are transmitted by a tick vector. The frequency of ehrlichiosis is increasing, which is ascribed to the increased awareness and diagnostic availability, as well as the expansion of regions populated with the most common tick vector – Amblyomma americanum (also known as the Lone Star tick).

Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum). Image Credit: Melinda Fawver / Shutterstock

Symptoms of the disease usually include fever, anorexia, headache and myalgia, with a relatively low incidence of rash (present only in 20% of affected individuals). The knowledge of disease epidemiology is vital, as early recognition may prevent a large number of cases (and thus avoid rare fatal outcomes).

Generally, the median age for acquiring ehrlichiosis is 51-53 years, while Caucasian males are the most commonly affected group. Even though cases of the disease are found year-round, the greatest number is observed between May and August, which coincides with periods of abundant populations of ticks and human open air recreation.

Epidemiology of Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis (caused by the species Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia canis) was initially described in 1986, and almost three thousand cases have been reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the last three decades. Even though the average incidence of this disease in the United States is 0.7 cases per million inhabitants, this estimation is based on passive surveillance and probably represents substantial underestimation of the actual incidence.

For example, in one seroprevalence study conducted on children it was demonstrated that 20% of infected individuals from endemic areas had detectable antibodies to Ehrlichia chaffeensis, without any previous history of apparent clinical disease. This is in line with the finding that more than two-thirds of all infections with causative agents of human monocytic ehrlichiosis are either without any symptoms or minimally symptomatic.

Akin to other tick-borne illnesses, the distribution of arthropod vectors and reservoirs in vertebrates highly correlates with the disease occurrence in humans. The predominant zoonotic cycle of Ehrlichia chaffeensis is comprised of infected white-tailed deer as the reservoir and Amblyomma americanum as the tick vector, both prevalent across southcentral and southeast United States.

This tick also has three feeding stages (known as larval, nymph and adult stages), and each developmental representative feeds only once. Transstadial transmission of Ehrlichia can be seen during nymph and adult feeding, because larvae are uninfected. Unlike some other species (most notably Rickettsia), Ehrlichia cannot be maintained via trans-ovarial transmission pathway.

Epidemiology of Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis

In the 1990s certain patients from Wisconsin and Michigan with a history of tick bite presented with a febrile illness similar quite similar to human monocytic ehrlichiosis. These cases were characterized by inclusion bodies in granulocytes rather than agranulocytes (monocytes), which is why this syndrome was initially named human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. After recent reclassification of Ehrlichia phagocytophilum to the genus Anaplasma, the disease has been renamed to human granulocytic anaplasmosis.

The annual number of human granulocytic anaplasmosis cases exceeds those of human monocytic ehrlichiosis, with an incidence case rate of 1.6 per million inhabitants in the U.S. As with Ehrlichia chaffeensis, different serosurveillence studies evince that asymptomatic disease is quite common. The disease is primarily caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum.

This disease is seen in Europe as well, where the majority of cases is found in central Europe (e.g. Slovenia) and Scandinavian countries (e.g. Sweden), though individual reports have come from other countries as well. Nonetheless, there is limited knowledge as to the exact epidemiological features and implicated animal reservoirs in Europe.

Different ticks transmit human granulocytic anaplasmosis in different continents; Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus are the predominant tick species in the United States, Ixodes ricinus in Europe, while Ixodes persulcatus transfers the infectious agent in Asia. Small mammals (such as White-footed mouse and Dusky-footed wood rat) are primary reservoirs of the disease.

Epidemiology of Ehrlichia ewingii

The epidemiology of Ehrlichia ewingii is usually addressed separately as there are certain problems with this species, such as the absence of specific serological tests and the lack of adequate reporting systems. What we do know is that most infections have been observed in immunosuppressed patients (after organ transplantation) and in those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

The primary vector for Ehrlichia ewingii is the Lone Star tick, as for Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Most human cases of the disease have been documented in Missouri, Oklahoma and Tennessee in the United States, although infection has been described in dogs and deer throughout the range of the tick that transmits the disease, suggesting that the infection with this specific species might be even more widespread.

Pathophysiology of the Disease

Infection with bacterial species causing ehrlichiosis occurs when the extracellular infectious form of the organism is taken up by the host cell. These infectious forms are either the elementary body or the dense core, and are taken up by the cell via a process known as endocytosis. Once inside the cell, the infecting organism divides and matures until it forms a reticulate body/reticulate core, and then a morula; these are then redifferentiated again into an elementary body/dense core so it can leave the infected host cell and spread further.

During this process, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma utilize a range of immune evasion mechanisms, such as suppression of apoptosis in host cells, down-regulation of recognition receptors in the host that could enable clearance of the infection, as well as modulation of cytokine and chemokine responses. Some species have a preference for granulocytic cells (Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Ehrlichia ewingii), while others target mononuclear phagocytes (Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia canis)

Furthermore, multisystem involvement is also a potential consequence, as microorganisms are found in the spleen, bone marrow, lymph nodes and peripheral blood. In fact, all the clinical manifestations are thought to be a result of a host inflammatory response to disseminated infection, rather than because of direct bacteria-induced damage.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with ehrlichiosis (regardless of the putative organism) clinically present with fever, chills, severe headache, confusion, malaise, nausea, vomiting, and generalized body aches. Respiratory symptoms such as cough may also be observed, but they are more common in adults than in children.

Symptoms are typically seen one to two weeks following a tick bite, with a median of nine days. The problem with tick bites is that they are usually painless, and therefore many people do not even remember being bitten. Due to immune suppression, secondary infections (usually caused by cytomegalovirus or fungi) are also frequent in severely diseased patients.

In approximately one-third of individuals with ehrlichiosis there is a visible rash that is maculopapular or petechial. The rash is more commonly observed in children and typically develops five days after fever ensues. If present, the rash typically spares the palms, soles and the face.

Akin to rickettsial infections, central nervous system involvement may occur in up to 20% of affected individuals, including dangerous manifestations like meningoencephalitis. Moreover, in some patients the disease may advance to acute respiratory distress syndrome or a shock-like presentation coupled with bleeding disorders and cardiovascular instability.

However, the overall death rate is substantially lower in ehrlichiosis when compared to rickettsial diseases. According to the data published by U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the mortality rates in patients who are seen by a healthcare professional due to ehrlichiosis range from 1% to 3%.

On the other hand, a large number of patients may be infected with Ehrlichia and Anaplasma, but do not come for medical evaluation; therefore, these percentages may be overestimations of mortality. Naturally, immunocompromised individuals, elderly and those previously treated with sulfonamide antibiotics are at higher risk of more severe disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Since ehrlichiosis is a multisystem disease characterized by protean manifestations (i.e. without pathognomonic and highly characteristic clinical features), the differentials are often quite broad. Initial symptoms are often generalized and somewhat vague, which is why the illness may first be diagnosed as a possible “viral syndrome” in the context of upper respiratory infection, gastroenteritis and/or meningoencephalitis.

A history of tick exposure or tick bite in the recent past can be elicited from a majority of patients, but it is important to emphasize that this feature may be absent in up to 30% of all cases. Therefore, pursuing other appropriate diagnostic procedures to confirm this disease is of the utmost importance.

Pancytopenia (i.e. an abnormally low count for all three types of blood cells) is a hallmark laboratory finding of human ehrlichiosis during the early days of the disease.

- leukopenia (mild or moderate) in 70% of patients (with the most significant decline being in the lymphocyte population) during the first week.

- Anemia in 50% of acute patients

- Low platelet count

- elevated liver transaminases

The next step towards accurate diagnosis is making blood smears from peripheral blood, cerebrospinal fluid or bone marrow, which are stained with Giemsa or Wright’s stains to detect specific bacterial structures known as morulae.

Albeit this technique is rapid, it is rather insensitive in comparison to other confirmatory tests, and particularly in immunocompetent patients who have extremely low bacterial loads in blood and body organs.

The Use of Serology

The most sensitive method of infection confirmation is a seroconversion or a 4-fold change in antibody titers during the convalescent phase of the disease.

Specific serologic testing of IgM and IgG antibodies to Ehrlichia chaffeensis or Anaplasma phagocytophilum by means of indirect immunofluorescence assay is considered the “gold standard” and thus the most frequently employed confirmatory test.

Nonetheless, serology has its limitations, and these include a negative IgG test and uninformative levels of IgM titers in 80% of affected individuals during the first week of the disease, a high false positive rate, seroconversion failures due to weak immune function, as well as alteration of antibody response because of early antibiotic treatment.

Molecular Diagnostic Procedures

Due to high specificity and sensitivity values, as well as a very rapid turnaround time, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) became the preferred test for confirming serology findings indicative of human monocytic ehrlichiosis and human granulocytic anaplasmosis.

The use of PCR is especially important in the detection of early stages of infection, when antibody levels are low or undetectable.

A large number of kits are commercially available for whole blood PCR testing, which enables rapid diagnosis in up to 85% of infected individuals. Recent advances in molecular research even allow multiplex testing that can identify several agents of ehrlichiosis from one test.

Laboratory Culture

Although the possibility of culturing Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species is also available to clinicians and researchers, the isolation of these organisms requires cell lines and typically takes 2-6 weeks of incubation.

The sensitivity of this approach for the isolation of Ehrlichia chaffeensis is very low when compared to PCR, but higher (and almost comparable to PCR) for Anaplasma phagocytophilum.

The major pitfall of the laboratory culture approach is the paucity of competent laboratories, since this technique necessitates unique and antibiotic-free cell culture methods that are not usually available in clinical microbiology laboratories.

In addition, prior treatment with doxycycline or some other antimicrobial drugs lowers the sensitivity of culture to a greater degree when compared with blood smear analysis or PCR.

Immunohistochemistry

This is another confirmatory technique and is especially valuable when the diagnosis is to be made before antibiotic treatment is begun, or at least within 48 hours of its initiation. It can also be applied to bone marrow and autopsy specimens.

All those factors have to be taken into account when assessing patients with suspected ehrlichiosis, which is the reason why some propose combining different diagnostic methods to increase the likelihood of early diagnosis. Naturally, clinicians always have to consider other diseases that have similar clinical and laboratory findings to ehrlichiosis.

Treatment Options for Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia canis, the causative agents of human monocytic ehrlichiosis, are susceptible to all tetracycline antibiotics and their derivatives. These drugs exhibit broad spectrum activity by binding to bacterial ribosomes and inhibiting protein synthesis by interrupting peptide chain formation. A plethora of other human pathogens (such as rickettsiae, borreliae, chlamydiae, as well as some mycobacterial and protozoal species) are susceptible to tetracyclines as well.

Treatment considerations for human granulocytic anaplasmosis are similar to those for human monocytic ehrlichiosis, with tetracyclines being very effective against Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Ehrlichia ewingii. The possibility of Babesia co-infection often has to be considered, which means monotherapy is sometimes not sufficient.

In both groups of diseases treatment response is usually rapid. Therefore, an alternative diagnosis should be considered if fever persists for more than 72 hours after the initiation of appropriate antibiotics. Even though research studies did not specifically address recommended treatment duration, many experts advocate continued antibiotics for 3-5 days after fever abates, and perhaps even longer (up to 14 days) if there were signs of central nervous system involvement. (Please see my comment at end of article)

A particular challenge for clinicians is ehrlichiosis in pregnancy, as tetracyclines are contraindicated in this population. Antibiotic sensitivity studies show that certain anti-tuberculous drugs have bactericidal activity in vitro against Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. This is also a viable and appropriate alternative approach in pregnant women.

Since clinical experience with other drugs that show activity in vitro is lacking, there are no fixed treatment recommendations for children younger than eight years of age, as well as for individuals who are hypersensitive to tetracycline drugs. Furthermore, there is no clinical data on the potential usefulness of adjunctive corticosteroid application to suppress the inflammatory manifestations of the disease.

Pertinent Prevention Strategies

Avoiding tick bites and removing any adherent tick immediately are the first steps in disease prevention. Individuals who reside in endemic areas are advised to wear long sleeves and light colored clothing during outdoor activities, since the latter permits easier visualization of crawling ticks. Adults at high risk of tick bites should apply repellents such as N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (commonly known as DEET) or permethrin to prevent this.

After visiting tick-infested regions, a careful inspection of body, hair and clothes should always be done with immediate removal of attached ticks. Research studies have demonstrated that a period lasting from 4 to 24 hours after infected ticks attach to the host is possibly essential for the successful transmission of Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. Hence, swift and thorough removal of attached ticks is of the utmost importance for preventing transmission and subsequent disease.

At the moment there are no commercially available or experimental vaccines for prevention of either human or veterinary ehrlichiosis. In conclusion, it has to be emphasized that the diagnosis of ehrlichiosis necessitates a high level of suspicion, which is why it is often made retrospectively, with potentially dire consequences for the affected individuals in rare cases.

Sources

- https://www.cdc.gov/ehrlichiosis/index.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28457353

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17582569

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441966/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC145301/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2882064/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4710445/

- Vanderhoof-Forschner K. Everything You Need to Know About Lyme Disease and Other Tick-Borne Disorders. John Wiley & Sons, 2004; pp. 104-132.

Sources for treatment and prevention

- http://www.antimicrobe.org/r01.asp

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28457353

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441966/

- https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/45/5/589/274600

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC145301/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4744069/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2882064/

- https://www.cdc.gov/ehrlichiosis/treatment/index.html

_________________

**Comment**

Lyme/MSIDS patients are often coinfected with numerous pathogens making them immunocompromised. Cortico-steroids are not recommended for this population. Also, as a rule, ILADS (International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society) recommends longer treatment and numerous antimicrobials due to the polymicrobial nature of tick-borne illness as well as the fact many of these pathogens are persistent.

For another great read: https://www.lymedisease.org/ehrlichiosis-tick-borne-disease-no-one-heard/ The author brings up a valid point about the potential of there being undiagnosed Ehrlichia behind a ME/CFS diagnosis in a subset of patients since it infects white blood cells and the mitochondria. The article also gives helpful percentages of symptoms and the following information:

Other symptoms of ehrlichiosis can include:

- Fever/chills and headache (majority of cases)

- Fatigue/malaise (over two-thirds of cases)

- Muscle/joint pain (25% – 50%)

- Nausea, vomiting and/or diarrhea (25% – 50%)

- Cough (25% – 50%)

- Confusion or brain fog (50% of children, less common in adults)

- Lymphadenopathy (47% – 56% of children, less common in adults)

- Red eyes (occasionally)

- Rash (approximately 60% of children and 30% of adults)

Other modes of transmission

Ehrlichia chaffeensis has been shown to survive for over a week in refrigerated blood. Therefore these bacteria may present a risk for transmission through blood transfusion and organ donation. It has also been suggested that ehrlichiosis can be transmitted from mother to child, and through direct contact with slaughtered deer. (14, 15)

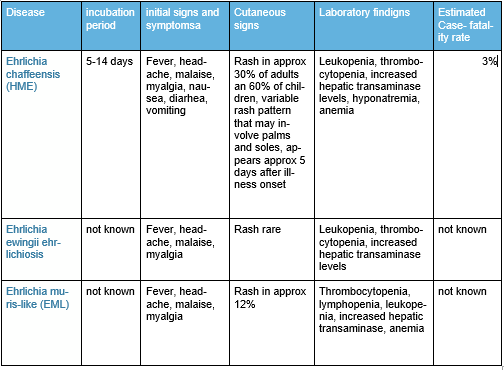

Summary of Ehrlichiosis

As you can see from this nifty table, much is UNKNOWN. This right here is another example of research begging to be done. The results would be practical, effectual, and essential in treating patients – unlike climate data which will only line the pockets of research institutions. Remember Zika? It caused a media blitz with research being done everywhere. As you can see from this article, Ehrlichia can be deadly and is spreading. Why no news and research?

https://madisonarealymesupportgroup.com/2018/07/24/oklahoma-ehrlichiosis-central/

https://madisonarealymesupportgroup.com/2018/03/09/dogs-ehrlichiosis/