Nov. 3, 2021

In 2013, the pain management clinic at a large teaching hospital diagnosed my then-15-year-old daughter with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). This was after 10 months of being referred to many pediatric specialists, none of whom could find an answer to her mysterious illness.

One of the hallmarks of ME/CFS is post-exertional malaise—profound fatigue following activity that is not restored by rest. Fatigue is also the most common symptom reported in patients with Lyme disease. (Aucott 2013, Johnson 2014)

At the time of my daughter’s diagnosis, she was mostly bedbound. An hour of homework would require a week of recovery. She had many symptoms of Lyme disease (fatigue, headache, light sensitivity, memory loss, heart block, POTS, swollen knee, muscle pain, nausea…the list goes on) but three separate standard tests for Lyme were negative.

In the absence of a definitive diagnosis, patients are often lumped into the category of ME/CFS—a complex and disabling syndrome. First defined by the CDC in 1988, the symptoms of ME/CFS have been recorded for centuries. (Holmes, 1988)

The million-dollar question?

There is no question that many infectious agents can trigger chronic illness. Past pandemics with infection-triggered chronic fatigue include: Russian influenza 1889, polio 1916, SARS-CoV-1 2003, Zika 2015, Ebola 2016, and more recently, COVID 2019.

But not everyone who contracts these diseases becomes chronically ill. As PolyBio researcher Amy Proal, PhD, said at the 2021 LymeMind conference, “The million-dollar question is why? Why do some patients go on to develop long-term, chronic symptoms and others do not?”

Even more puzzling is why do patients infected with completely different pathogens (viruses, bacteria, parasites) have so many of the same flu-like symptoms?

For example, the pathogens that cause COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2, a virus) and Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi, a bacterium) are vastly different. However, the chronic symptoms they leave behind are nearly identical: fatigue, brain fog, headaches, sensory issues, cognitive impairment, memory loss, sleep impairment, heart issues, muscle and joint aches/pain. The primary difference here being the respiratory symptoms among those with COVID-19. (Proal & VanElzakker 2021)

During the LDA/Columbia Lyme Conference, Dr. John Aucott, of Johns Hopkins University, reviewed several potential causes of “long-haul” symptoms for infectious diseases such as Lyme disease and COVID-19. These include: 1) persistent antigens and/or persistent infection; 2) immune inflammation and dysregulation; 3) neural network alterations.

One pathway that links all three of these elements (infection, inflammation, nervous system) together is called the vagus nerve. And one theory gaining recognition is the vagus nerve infection hypothesis, first proposed by Harvard neuroscientist Michael VanElzakker in 2013. (VanElzakker, 2013)

Because we know that Borrelia can infect the brain and the cranial nerves, this theory may explain why some patients remain ill following treatment for Lyme disease. (Gadila, 2021)

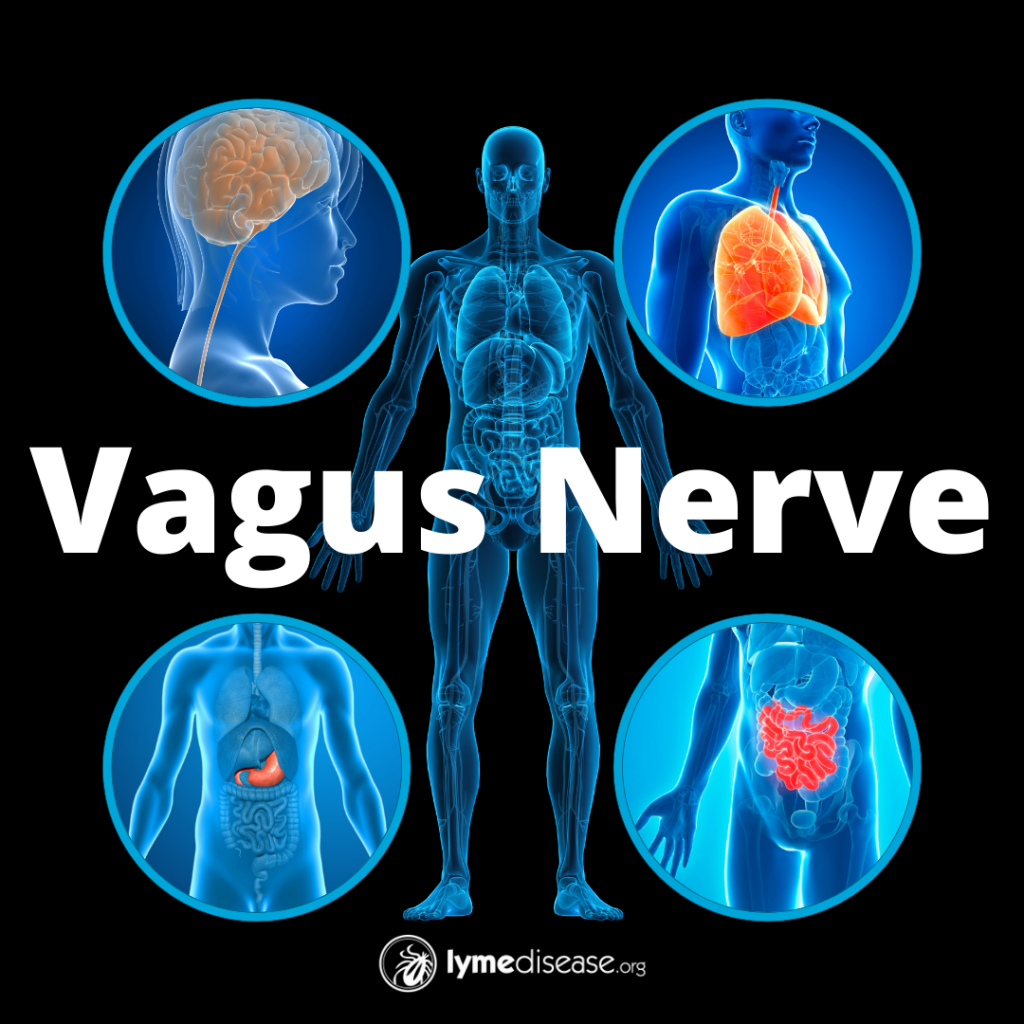

What is the vagus nerve?

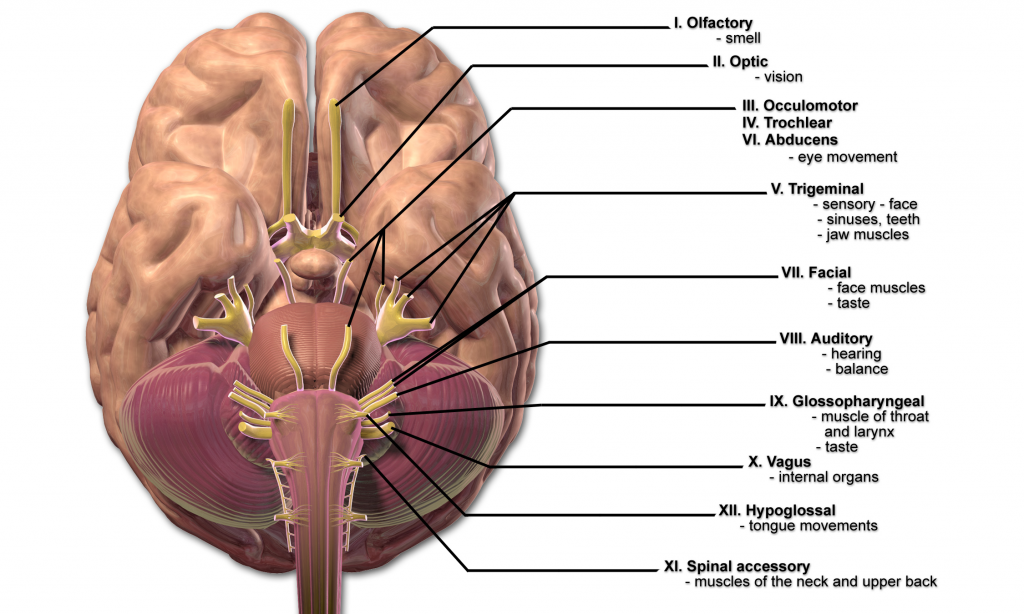

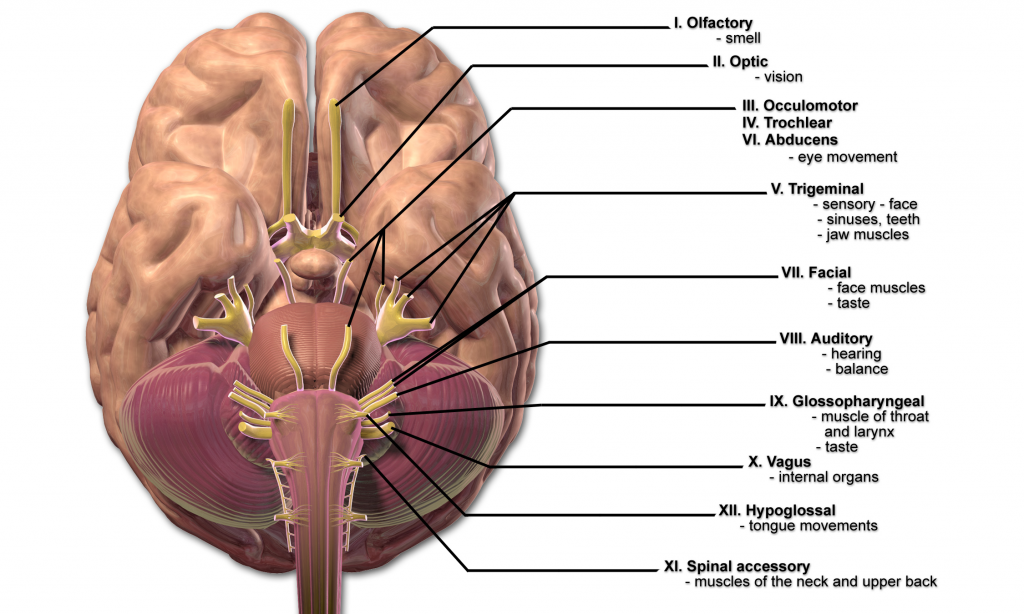

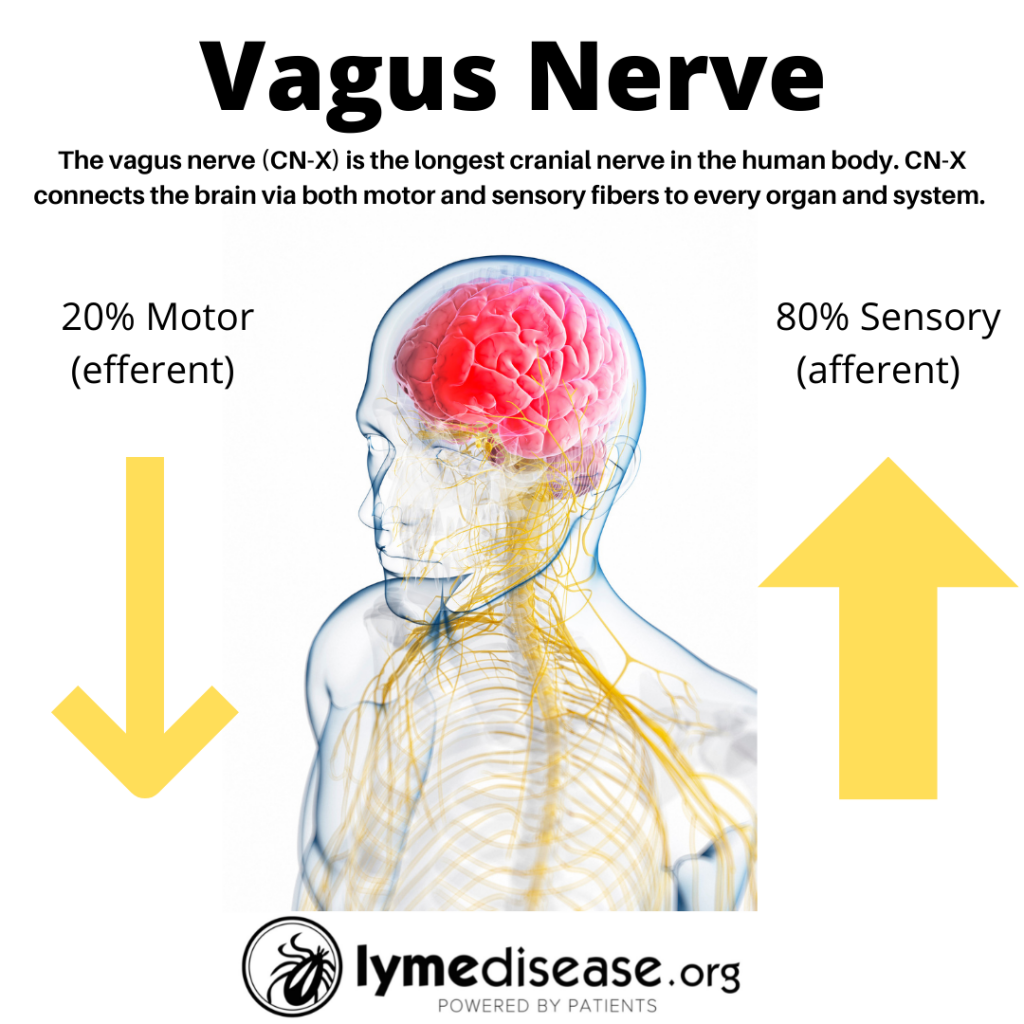

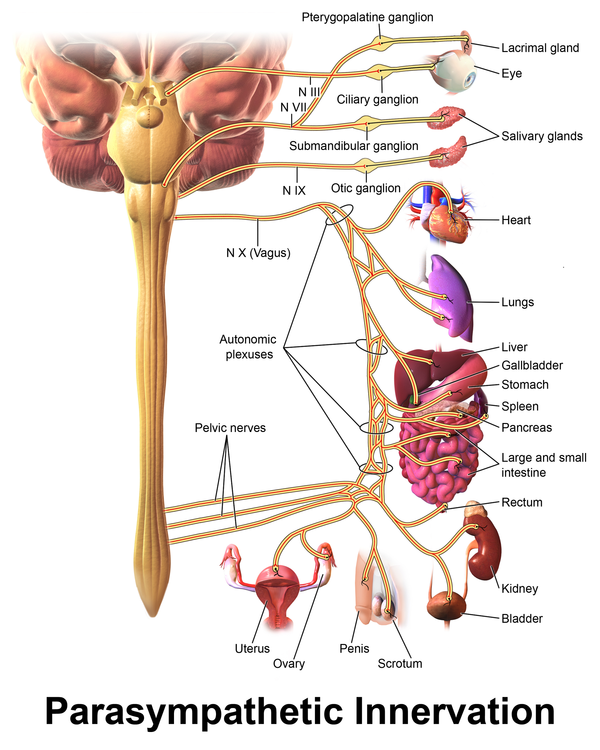

The vagus nerve is the tenth (X) of 12 cranial nerves originating in the brain, denoted as CN-X. It originates from a portion of the brain responsible for autonomic function.

Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014”. WikiJournal of Medicine 1

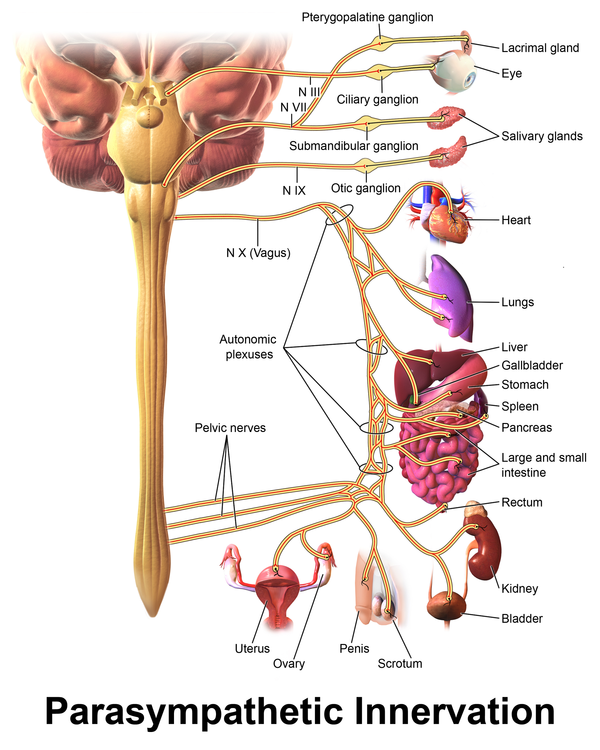

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is the part of the nervous system that functions without you having to think about it. It regulates bodily functions such as breathing, heart rate, digestion, and blood pressure.

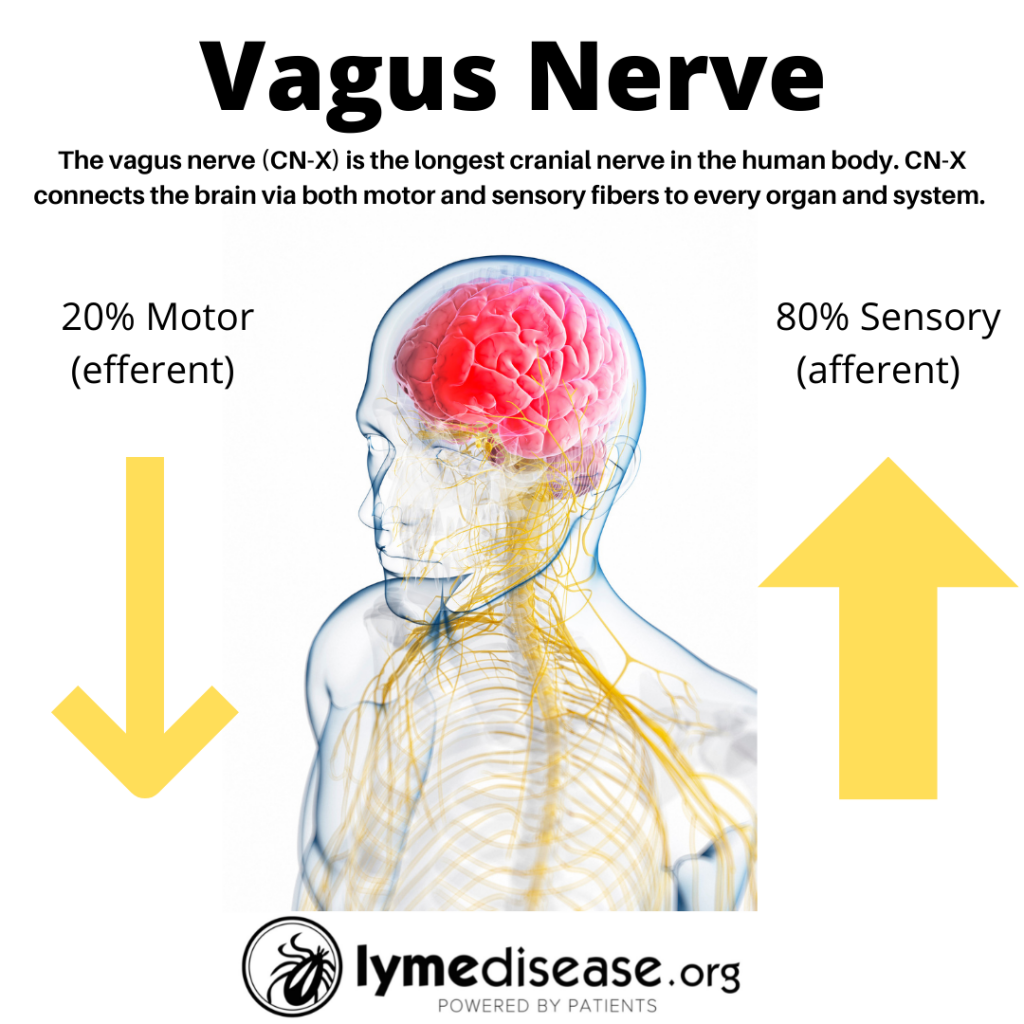

The vagus is the longest cranial nerve in the body. It innervates (supplies nerves to) every major trunk organ including the pancreas, liver, spleen, heart and bladder, along with the gastrointestinal lining and lymph nodes (Kenny and Bordoni, 2019). The Latin word vagus means “wandering.”

Twenty percent of the vagus nerve fibers lead away from the brain into the body (efferent), while 80 percent of the nerve fibers send signals from various points in the body back to the brain (afferent).

The most important function of the vagus nerve is afferent signaling. This is information brought from the inner organs—such as gut, liver, heart, and lungs—to the brain. Thus, our inner organs are a major source of sensory information to the brain.

The limbic system, amygdala and insular cortex are important central regions that are affected by vagus nerve signals. These areas of the brain are involved in regulating emotions, behavior, memory, and energy.

How does the vagus nerve affect autonomic function?

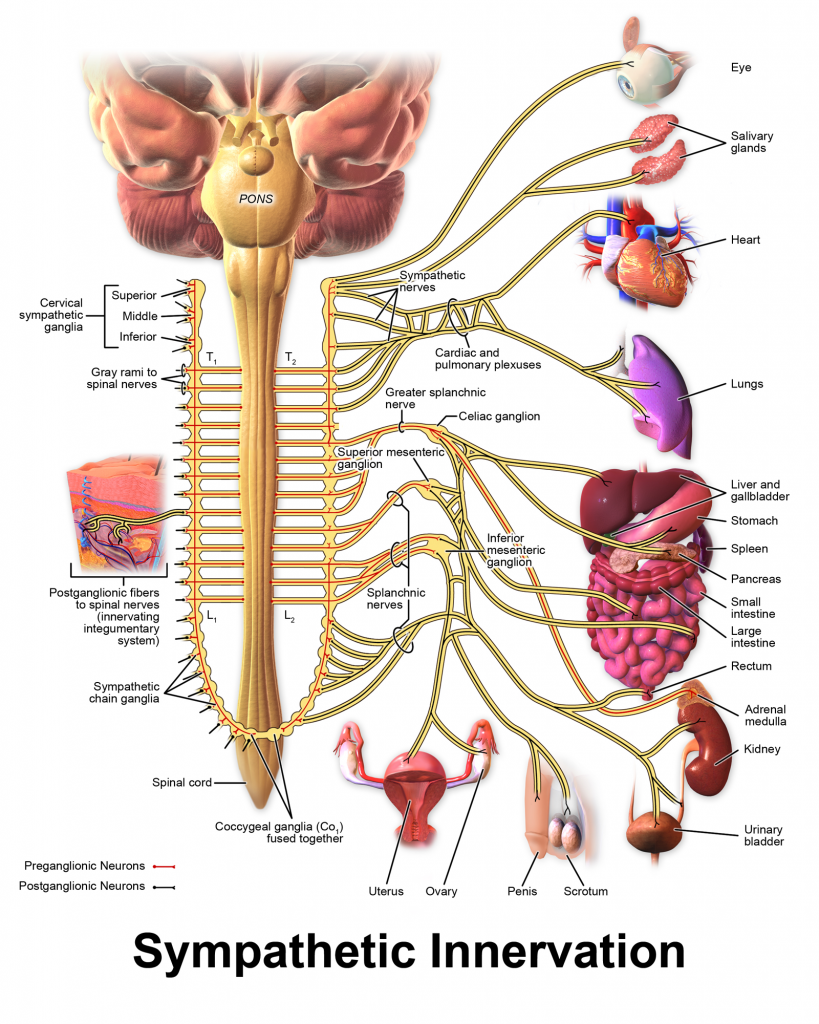

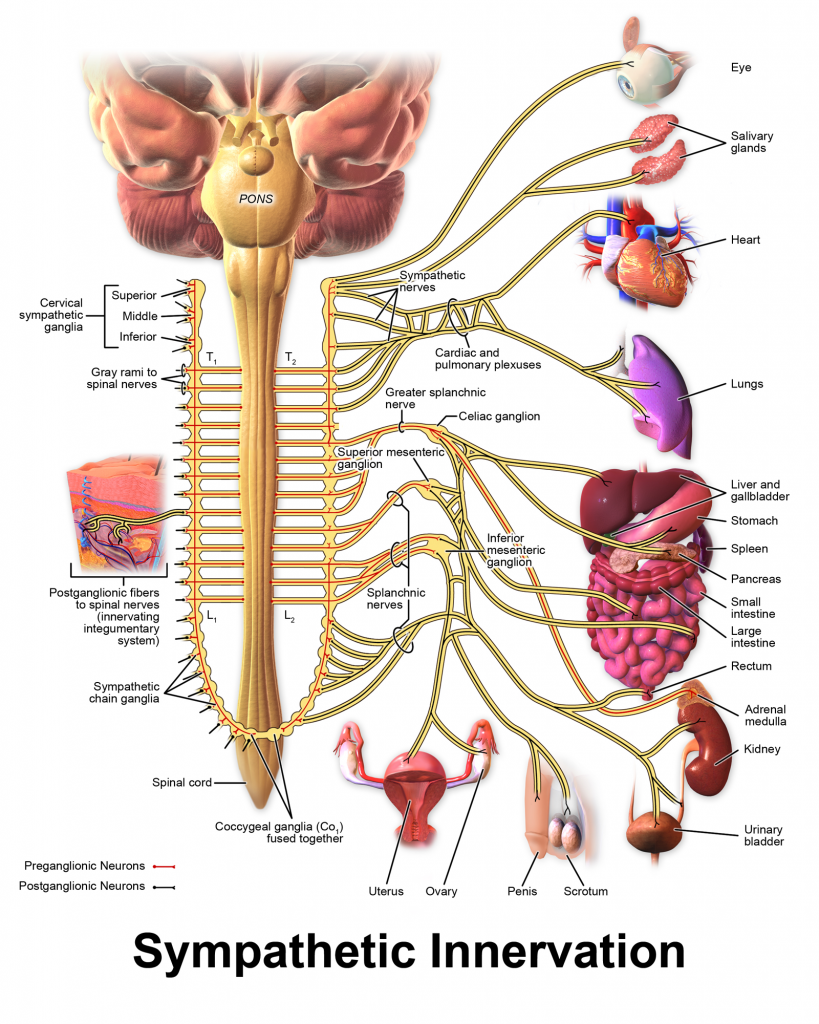

The ANS is divided into the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system.

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is often referred to as the “fight or flight” or “excitatory” system. It is a primitive system designed to respond and help you get out of danger.

Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014”. WikiJournal of Medicine 1

The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), commonly known as the “rest and digest” or “inhibitory” system, promotes the opposite response of the SNS.

Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014”. WikiJournal of Medicine 1

Both the SNS and PNS are involved when you become sick. Because we cannot feel, smell or see pathogens, the body uses the vagus nerve to sense when we are ill and send a message to the brain. This message triggers an adaptive response to the infection called “sickness behavior” or the “sickness response.”

However, if the infection or inflammation persists, this sickness response can become chronic, resulting in ME/CFS type symptoms.

How the vagus nerve causes flu-like symptoms

When a pathogen is detected, mast cells and glial cells release inflammatory markers and cytokines that trigger an immune response. The vagus nerve senses these markers and sends a message to the brain. This causes flu-like symptoms: fever, fatigue, headache, sleep problems, loss of appetite, muscle/joint pain, nausea, autonomic dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and others.

This constellation of symptoms causes a sickness response that is designed to make us rest. Ideally, during this rest period our body can use all its energy to fight the infection and recover from the illness. Farmers and pet owners may recognize such sickness behavior in their sick animals, as well.

For years, it has been thought that Borrelia spread to the nervous system via the blood stream. A recent publication indicates that central nervous system involvement in Lyme neuroborreliosis may be a result of Borrelia moving from the skin to the spinal cord via peripheral nerves. (Ogrinc, 2021)

The vagus nerve may be a pathway for this type of infection.

Vagus nerve infection hypothesis

The vagus nerve infection hypothesis theorizes that the chronic flu-like symptoms of ME/CFS are an exaggerated version of normal sickness behavior triggered by infection of the vagus nerve.

In theory, any infectious agent with a preference for nervous tissues (neurotropic) can cause a vagus nerve infection, including Borrelia.

The gut-brain axis

The gut is the largest organ innervated by the vagus nerve, making it a particularly important sensory organ. (Breit, 2018) Gut bacteria (both good and bad) communicate through the microbiota-gut-brain axis in a bidirectional way that directly involves the vagus nerve. (Bonaz, 2018)

A huge amount of data has highlighted a potential role of microbial dysbiosis (an imbalance of bacteria in the gut) in various chronic disorders (Lynch and Pedersen, 2016).

The standard treatment for Lyme disease involves the use of antibiotics, which can adversely affect gut bacteria. Researchers at Northeastern University are currently looking at how the microbiome may contribute to the chronic symptoms of Lyme.

Not only can imbalance of the microflora or microbiome in the gut cause inflammation that triggers the vagus nerve, but it can also contribute to a leaky blood-brain barrier contributing further to neurological and psychological symptoms in Lyme.

Treatment

Obviously, if there is an infection present it should be treated appropriately. Lyme disease is often accompanied with co-infections carried by the same tick, a separate tick bite, or possibly even a prior latent viral infection. Thus, treatment may involve antibiotics, anti-parasitics and antivirals.

As a benefit, some of the standard medications for Lyme disease have anti-inflammatory effects on the nervous system. However, not all of them are able to cross the blood-brain barrier.

For example, minocycline crosses the blood-brain barrier and in addition to anti-microbial activity, it has been shown to have anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic activities, inhibition of proteolysis, angiogenesis and tumor metastasis-inflammatory as well as neuro-protective properties. (Garrido-Mesa, 2013)

Self-Help

Following treatment, or even during treatment, if you are exhibiting symptoms of dysautonomia (dysfunction of the ANS), you may want to try some of the non-prescription practices that worked for my daughter.

- Anxiety: Restorative yoga

- Depression: Professional counseling, cognitive behavior therapy

- Dizziness: Lie down, apply ice pack to forehead &/or back of neck

- Fatigue: Pacing, energy conservation

- Gastroesophageal reflux: Raise the head of the bed with 2-4 inch blocks.

- Gastroparesis: Abdominal massage

- Gastrointestinal pain: Anti-inflamatory diet, low histamine diet

- Insomnia: Mindfulness meditation, diaphragmatic breathing

- Low blood pressure: Increase fluids, add salt to diet

- Pain: Moist heat, positioning, gentle massage, Epsom salt baths

- Postural orthostatic hypotension (POTS): Thigh-high 15-20 mmHG compression stockings

- Stress: DNRS

- Swollen lymph nodes: Lymph drainage massage

- Weakness: Stretching, gentle exercises, pool therapy

Another technique is the use of external (transdermal) vagus nerve stimulation, similar to a home TENS unit. (Diedrich 2021)

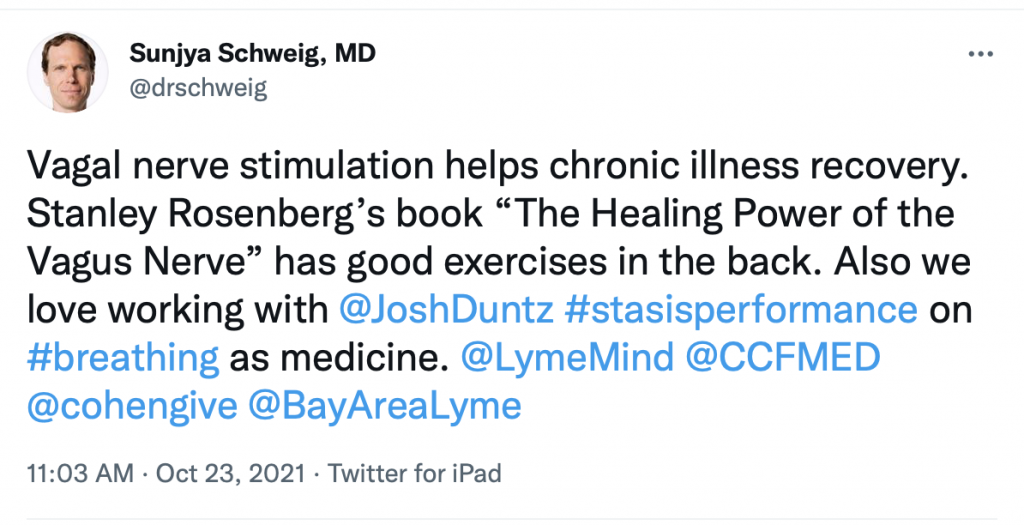

During the LymeMind conference, Dr. Sunjya Schweig, an integrative medicine specialist, tweeted this:

Stanley Rosenberg’s 2017 book “Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve: Self-Help Exercises for Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, and Autism” offers a simple explanation of Stephen Porges’s polyvagal theory.

Rosenberg’s book draws on more than 30 years of his experience as a hands-on craniosacral therapist and Rolfer. He offers immediate self-diagnostic and treatment techniques that can be done from the comfort of your home.

Main takeaway

Whether you have an active infection or the remnants of a previous infection, the vagus nerve may be contributing to your ongoing symptoms. Learning to recognize those symptoms and adding a few simple self-help techniques may help in your healing journey.

LymeSci is written by Lonnie Marcum, a Licensed Physical Therapist and mother of a daughter with Lyme. She serves on a subcommittee of the federal Tick-Borne Disease Working Group. Follow her on Twitter: Email her at: lmarcum@lymedisease.org.

References

Aucott JN, Rebman AW, Crowder LA, Kortte KB. Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome symptomatology and the impact on life functioning: is there something here? Qual Life Res. 2013 Feb;22(1):75-84. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0126-6. PMID: 22294245; PMCID: PMC3548099.

Azcona Sáenz J, Herrán de la Gala D, Arnáiz García AM, Salas Venero CA, Marco de Lucas E. (2021) Atypical bacterial infections of the central nervous system transmitted by ticks: An unknown threat. Radiologia (Engl Ed). Sep-Oct;63(5):425-435. doi: 10.1016/j.rxeng.2021.07.002. PMID: 34625198

Bonaz, B., Bazin, T., & Pellissier, S. (2018). The Vagus Nerve at the Interface of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Frontiers in neuroscience, 12, 49. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00049

Breit S, Kupferberg A, Rogler G and Hasler G (2018) Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain–Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 9:44. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044

Coughlin et al. Imaging glial activation in patients with post-treatment Lyme disease symptoms: a pilot study using [11C]DPA-713 PET

Diedrich A, Urechie V, Shiffer D, Rigo S, Minonzio M, Cairo B, Smith EC, Okamoto LE, Barbic F, Bisoglio A, Porta A, Biaggioni I, Furlan R. (2021) Transdermal auricular vagus stimulation for the treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci. Sept29;236:102886. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102886. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34634682.

Ford, L., & Tufts, D. M. (2021). Lyme Neuroborreliosis: Mechanisms of B. burgdorferi Infection of the Nervous System. Brain sciences, 11(6), 789. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060789

Gadila SKG, Rosoklija G, Dwork AJ, Fallon BA and Embers ME (2021) Detecting Borrelia Spirochetes: A Case Study With Validation Among Autopsy Specimens. Front. Neurol. 12:628045. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.628045

Garrido-Mesa, N., Zarzuelo, A., & Gálvez, J. (2013). Minocycline: far beyond an antibiotic. British journal of pharmacology, 169(2), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.12139

Holmes GP, Kaplan JE, Gantz NM, Komaroff AL, Schonberger LB, Straus SE, Jones JF, Dubois RE, Cunningham-Rundles C, Pahwa S (1988). “Chronic fatigue syndrome: a working case definition”. Annals of Internal Medicine. 108 (3): 387–89. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-108-3-387. PMID 2829679.

Johnson L, Wilcox S, Mankoff J, Stricker RB. 2014. Severity of chronic Lyme disease compared to other chronic conditions: a quality of life survey. PeerJ 2:e322 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.322

Kenny BJ, Bordoni B. (Updated 2021) Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 10 (Vagus Nerve) In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537171/

Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 15;375(24):2369-2379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1600266. PMID: 27974040.

McCusker, R. H., & Kelley, K. W. (2013). Immune-neural connections: how the immune system’s response to infectious agents influences behavior. The Journal of experimental biology, 216(Pt 1), 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.073411

Ogrinc, K., Kastrin, A., Lotrič-Furlan, S., Bogovič, P., Rojko, T., Maraspin, V., Ružić-Sabljić, E., Strle, K., Strle, F. (2021) Colocalization of radicular pain and erythema migrans in patients with Bannwarth’s syndrome suggests a direct spread of borrelia into the central nervous system, Clinical Infectious Diseases, ciab867, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab867

Proal AD and VanElzakker MB (2021) Long COVID or Post-acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): An Overview of Biological Factors That May Contribute to Persistent Symptoms. Front. Microbiol. 12:698169. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.698169

VanElzakker MB. (2013) Chronic fatigue syndrome from vagus nerve infection: a psychoneuroimmunological hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. Sep;81(3):414-23. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.05.034. Epub 2013 Jun 19. PMID: 23790471.

VanElzakker MB, Brumfield SA and Lara Mejia PS (2019) Neuroinflammation and Cytokines in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): A Critical Review of Research Methods. Front. Neurol. 9:1033. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01033