Novel Rickettsia Species Infecting Dogs, United States

https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/12/20-0272_article

Volume 26, Number 12—December 2020

Novel Rickettsia Species Infecting Dogs, United States

Abstract

In 2018 and 2019, spotted fever was suspected in 3 dogs in 3 US states. The dogs had fever and hematological abnormalities; blood samples were Rickettsia seroreactive. Identical Rickettsia DNA sequences were amplified from the samples. Multilocus phylogenetic analysis showed the dogs were infected with a novel Rickettsia species related to human Rickettsia pathogens.

____________________

Important quote from study:

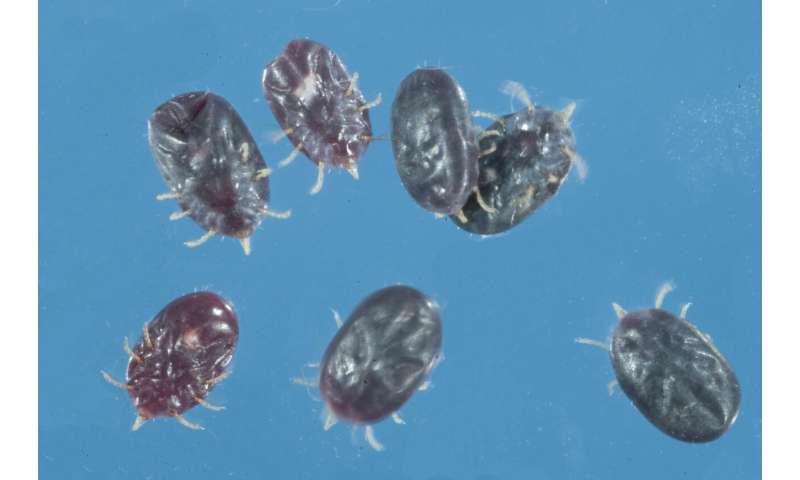

The cases were geographically distributed among 4 states; the dogs resided in Illinois, Oklahoma, and Tennessee, but the dog from Illinois had traveled to a tick-infested area of Arkansas. The tick species were not identified, but ticks common to these states include Amblyomma americanum, Dermacentor variabilis, and Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato, all of which are known to transmit Rickettsia (3). Haemophysalis longicornis, an invasive tick species recently confirmed in the United States, including in Tennessee and Arkansas, should be considered a potential vector for Rickettsia spp. (9,10).

Based on serologic cross-reactivity, presence of ompA, and phylogenetic tree analysis, the new Rickettsia sp. is an SFG Rickettsia, phylogenetically related to human pathogenic R. heilongjiangensis and R. massiliae, with only 95% identity to each (11,12). Thus, we report a previously unknown and unique Rickettsia sp. with clinical significance for dogs and potentially humans.

Because this novel Rickettsia cross-reacts with R. rickettsia on IFA, it could be underdiagnosed and more geographically widespread. Studies aimed at identifying the tick vector, potential animal reservoirs, and prevalence are ongoing. These 3 canine rickettsioses cases underscore the value of dogs as sentinels for emerging tickborne pathogens (13,14)

For more:

https://madisonarealymesupportgroup.com/2019/11/14/study-shows-ticks-can-transmit-rickettsia-immediately/ ..ticks can transmit infectious Rickettsia virtually as soon as they attach to the host.

- The Asian long-horned tick transmits Lyme disease, SFTS, spotted fever rickettsiosis (RMSF in a lab setting), Anaplasma, & Ehrlichia: https://madisonarealymesupportgroup.com/2018/06/12/first-longhorned-tick-confirmed-in-arkansas/